Home / Course Design

Decisions and then Design...

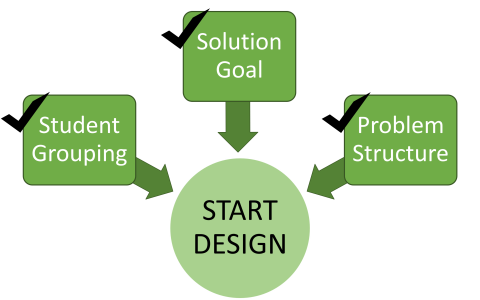

You probably have at least a vague idea of how your course and project will run, but before you start the actual design process, you need to know about the essential basic choices you must make, with regard to designing an interdisciplinary course. These include: how to group students; the solution goal; and the complexities of the different structures of project-designs you could choose. Your choice will affect the student’s learning process, as well as your teaching activities and assessment.

1. Student Grouping

Mixed Disciplinary vs Mono-disciplinary Groups

Interdisciplinary project-based courses are usually collaborative in nature, i.e. students from different disciplines are put together in project groups in order to combine their expertise in productive ways. However, interdisciplinary collaboration is the not the only option. A mono-disciplinary approach is also possible in which students are not from different disciplines and are tasked with the job of incorporating material from another discipline into their own, and/or acquiring skills in another discipline. A mixed collaborative vs. a mono-disciplinary structure, are quite different in terms of the team type skills they might require, resulting in different educational affordances. A mono-disciplinary structure for instance can train students well in their ability to understand another discipline and its intersection with their own.

2. Solution Goal

Integrated vs Multidisciplinary Solutions

2. Solution Goal

Integrated vs Multidisciplinary Solutions

The goal of integration is often considered paramount to interdisciplinary work. For integrated solutions, methodological approaches are combined to generate blended, but novel approaches. These are challenging to achieve, but thought to have great pay-off in learning. Most often, cross-boundary work is actually more multidisciplinary in character; a problem is divided into disciplinary tasks and then solved within disciplinary perspectives, and recombined at the end. Both modes are legitimate, and both can have educational value. Integrated solutions are harder to achieve and students may not progress so far; achieving them requires high levels of metacognitive skill development and team-based coordination. On the other hand, students engaged in multidisciplinary research may get further on the technical sides of their projects and processes by collating disciplinary information. Aiming for multidisciplinary solutions can be useful for training students in using their own methodologies in an interdisciplinary context, rather than aiming for innovation. Of course the solution-type can be left open to students, so that autonomy is still maintained.

3. Problem Structure

Open vs Closed

Selecting and defining the type of project or challenge with which you wish the students to engage, is an integral step. Furthermore, one has many additional contextual factors to consider such as maturation, level of independence or risk aversion of the students. Here, we begin to describe the various forms of projects, as well as some of the benefits and burdens associated with them.

These types of projects, usually involve an external stakeholder or a societal problem that is ill-defined. This leaves the student to unravel the true problem and attempt to offer proposals for solutions with limited directives, i.e. critical questions from tutors as opposed to hints on ideal trajectories. They usually undergo the “engage, investigate, act” framework associated with challenge based learning. Open-ended projects give students the freedom to lead their own learning journey, but often this is incidentally in 21st century skills, rather than advancement in theoretical and disciplinary depth.

Students: can feel overwhelmed and set adrift, decision making can be challenging and task paralysis is commonplace due to the perceived sheer enormity of a task. May experience teamwork problems such as uneven distribution of work or communication issues.

Teachers: “Front heavy” time investment and support in training students to follow the processes involved in first, unpacking then tackling the challenge. After some time, students begin to understand what is expected of them, but carefully choreographed and intense skills training at the beginning phases, is essential for success of the project. Goals are less content focused, more process orientated.

With projects like these, which can also have an external stakeholder or a societal problem, they are more narrow in description and focus attention on specific areas where solutions can be found. For example, an open-ended project may ask students to enhance sustainability in the aviation sector, where as a less open-ended project would ask students to offer solutions to enhance sustainability in the aviation sector, by focusing on commercial airlines’ need to be more innovative in the reduction of aeroplane mass. Students have the freedom to lead their own learning, but it is in a more directed manner that can help them to focus, and help teachers to better plan possible supplementary or just-in-time classes within a relevant theme, that can actually have an impact on the outcomes.

Students: have autonomy to choose learning path, even though they still have to make decisions on how to solve the challenge. Courses and teacher scaffolding supply them with the knowledge they need, on which to base their ideas. Teamwork issues may still exist. With focused challenges, certain disciplines may be left out or become redundant with regard to claiming an impactful role – this can demotivating for some students.

Teachers: More substantial planning beforehand is possible, intensity of support is more evenly distributed over the course as opposed to open-ended projects. Relevant theory can be introduced to enhance students’ base knowledge to tackle the challenge, thereby producing cognitive advancement in knowledge as well as 21st century skills. Some disciplines may be redundant in this type of project, therefore careful consideration that all who are involved can actually play a meaningful role, is imperative.

These types of projects allow for less creativity and autonomy for students, but allow teachers to guide students to reach desired learning outcomes, which can include interdisciplinary ones (e.g. the ability to combine two specific methodological approaches). Success criteria and transparent assessment rubrics clearly indicate what students need to achieve to have an acceptable project. Courses and workshops feed the knowledge and skills necessary to reach the goals and complete the challenge. Furthermore, roles can be carefully curated according to discipline and personal talent. Some freedom in creativity is of course allowed, but generally, all output will be of a similar theme.

Students: students do not necessarily have to think out of the box and lack of autonomy may reduce motivation if the chosen theme is considered boring. However, students are facilitated to develop both content knowledge as well as process skills in a more constructively aligned manner.

Teachers: finding a suitable theme that can suit all students is a challenge. Planning is very stable and each part of the course is fully mapped out from the start, allowing for clear constructive alignment.

Design... Begin with the end in mind

Where do you usually start when you design a course?

Often teachers will answer, “with the content.” This is perfectly understandable, as we think of which topics we must cover and how they can be arranged according to context, etc. However, starting your course design with the clear articulation of the learning objectives, helps teachers to prioritise what students will be able to know and do by the end of the course, as opposed to starting with textbook or a list of topics to be covered.

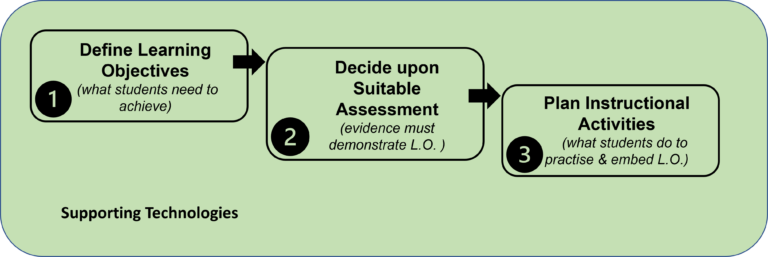

These steps, below, will take you through the backward design process, from an interdisciplinary perspective. Under this section we provide some more specific course design tools and resources for interdisciplinary course design.

THE COURSE DESIGN PROCESS

On this page you will start with the ‘end in mind’. In other words, what do you want your students to have achieved by the end of the course? You can also refresh your knowledge on some educational theory and then continue to the first phase of course design – defining and clarifying your learning objectives.

If you are not yet ready to define your learning objectives, and just want to see which skills are important for interdisciplinarity, you can start with our framework of skills.

After you have carefully established your interdisciplinary learning objectives, the next step is to plan your assessment. Using an assessment scheme can help you to ensure you cover your learning objectives according to the desired weightings and that the more important criteria get an appropriate share of the assessment.

After you have carefully established your interdisciplinary learning objectives, the next step is to plan your assessment. Using an assessment scheme can help you to ensure you cover your learning objectives according to the desired weightings and that the more important criteria get an appropriate share of the assessment.

What our students are actively learning and applying over the duration of the course must be directly related to the learning objectives and also be in line with how they will be assessed. Are the learning activities and facilitated moments appropriate for the levels we wish them to achieve? It is important to ask ourselves – are our students busy, or are they busy learning?

We have created, collected and borrowed some ready-made resources for you to implement directly into your sessions. As a starting point, we hope that these resources can be built upon and enhanced according to your needs and learning contexts.

There are a plethora of learning technologies that can aid with making your learning sessions more interactive and help you to save precious time in creating resources and scaffolds for you students. We have collated a variety of options for you, here.

There are a plethora of learning technologies that can aid with making your learning sessions more interactive and help you to save precious time in creating resources and scaffolds for you students. We have collated a variety of options for you, here.

FURTHER COURSE DESIGN ENHANCEMENTS

Problem-Design Heuristics

A good starting point for thinking about how to design a problem task which affords interdisciplinary engagement.

Integrative Modeling Approaches

Certain scientific methods support interdisciplinary engagement. Problems can be design with these in mind.