Home / Course Design / Instructional Activities

Step 3: Instructional Activities

What is the best format of instruction for an interdisciplinary course that needs to assess output as well as process?

When planning our interdisciplinary instructional activities, we need to think about how the teacher and student will be actively involved over the duration of the course. These are the aligned activities that prepare the students to attain the learning objectives and support them to prove their cognitive advancement, through the assessment.

In this section, you may get some ideas on what format your course could take, for examples of actual activities, please go to the Student Tasks page.

Selecting the Format of your Interdisciplinary Course

The medium-term nature of course planning allows educators to outline, describe, cohesively link and build upon themes, within the programme (bigger picture) and the course. This, with the goal to facilitate teaching and learning moments that enable students to reach the intended learning outcomes at the desired level. There are various established formats of education that are conducive to interdisciplinary learning, here we shall focus on the proven and ‘up and coming’ methods that you might consider appropriate according to your context.

Team Learning

Oftentimes, researchers and lecturers are specialists in their fields, but can lack the confidence to support the team process that is inextricably coupled to group work. It is assumed that the students will learn along the way and master the necessary 21st century skills incidentally, over the course of the project. This is not necessarily the case, and much frustration and disappointment can be avoided if students are supported to work effectively in a team, for example, on how to communicate across disciplines and give constructive feedback. Refer to our Team Skills on the Student Tasks page to inspire you on how to include team skill support within your course.

It is especially important at the beginning phases of group work, to facilitate moments when students can be guided on how to think from another disciplines’ perspective. It is important for them to establish expectations and create a common understanding and language. A well established, own-disciplinary grounding for individual students is an added advantage, as teachers can utilise this disciplinary-knowledge resource within the group, to propagate and embed new perspectives. The ‘team contracts’ and ‘competence triangle’ activities are provided in the Student Tasks section, and should give a good start for teammates to understand each other.

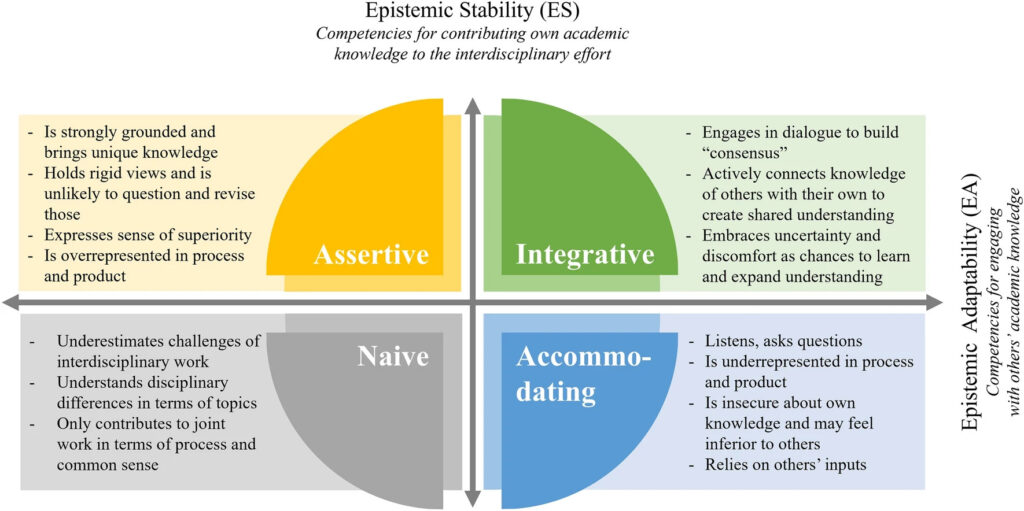

An interesting representation of personal and epistemic factors to consider before assuming readiness of students to experience interdisciplinary exercises is shared here (Horn, 2022). The full article is referenced below.

Due to the increasing internationalisation of tertiary education institutes and workplaces, intercultural appreciation and understanding is seen as a key 21st century skill. Incorporating these themes and allocating precious time within a course can be a challenge, but by cleverly weaving chosen topics within your lessons, the learning can be framed as incidental as opposed to a few dedicated stand alone sessions focusing on intercultural awareness. A great example created by Leonie Krab-Hüsken and LinLin Pei from the University of Twente, is shared below.

(Insert link to site and SEFI Article)

Due to the mixture of disciplines and talents within the group, there is ample opportunity for students, as experts in one field, to teach their novice teammates about their particular disciplines. This is of course easier if all students have a solid epistemic stability, but if not, knowing where to find answers and contrasting ways of working can provide learning opportunities for all involved. Peer learning can be facilitated through tutors who can nudge individuals to share their knowledge and skills throughout the group work process, or moments can be formally facilitated as in the ‘knowledge-based concept mapping’ and ‘perspective taking task’ found on the Student Tasks page.

Allowing students the autonomy to choose certain directions within their course and giving them the responsibility to take charge of their learning is not only motivating, but builds independence and reflective behaviour – if facilitated correctly. Offering students choices on how they can be assessed or allowing them to contribute to a section of the assessment rubric are some examples. Below are educational formats that inherently stimulate self-directed learning.

Project and Problem Based Learning

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is a student-centred pedagogy in which student learning occurs by finding solutions to complex real-world problems in a collaborative team environment (Barrett, 2005; Barrows & Tamblyn, 2016). PBL is considered a constructivist approach to instruction because it promotes collaboration and student autonomy, while being supported by tutor facilitation (Schmidt et al., 2016). The primary aim of PBL is not necessarily reaching a defined solution but rather the development or improvement of skills and competencies.

Project-Based Learning (PBL) is a student-driven, interdisciplinary and teacher-facilitated pedagogy with an active and experiential approach to learning as learners pursue knowledge by asking questions and investigating a subject that have piqued their natural curiosity, over an extended period of time (Bell, 2022). It is an enquiry learning approach as students develop a question, they carry out research under the teacher’s supervision and their discoveries are shared by creating a project. Project-based learning is rooted in the overall idea of “learning by doing” proposed by Dewey (1938) who also emphasised that the core value of the approach is student choice, while the teacher is a mere facilitator of the learning process.

The above approaches’ terms are often used interchangeably. Aside from their official definitions, the spirit of this format is to enable a group of students to apply knowledge and skill towards realistic contexts. They are empowered to make decisions on how they can tackle the project, and sometimes have the autonomy to choose to accept or decline scaffolding provided by facilitators. The groups are usually self-managed and the responsibility to ensure the process is performed professionally, falls on them. Educators can certainly enhance the process experience for the students – this is mentioned in the Team Learning section, above.

Two examples of challenge based courses, that were analysed for the STRIPES project are:

Related Case Studies

Discrete Structures & Algorithms

Short description

Consumer Products

Short description of case study

Challenge Based Learning

Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) is a learning framework according to which knowledge is gained by solving relevant, real-world challenges. CBL is most commonly defined as “a learning experience where knowledge is constructed through the identification, analysis and design of a solution to a sociotechnical problem. The learning experience is typically multidisciplinary, involves different stakeholder perspectives, and aims to find a collaboratively developed solution, which is environmentally, socially and economically sustainable” (Malmqvist et al., 2015). It is established on the foundation of aligned pedagogies such as experiential, enquiry and active learning (Gallagher & Savage, 2020). CBL’s most prominent element is that it is linked to societal challenges and students are encouraged to step outside of their academic bubble and consider further stakeholders in wider society with greater potential for impact, as a result.

Two examples of challenge based courses, that were analysed for the STRIPES project are:

Related Case Studies

Science to Society I

Short description of case study

Trans-disciplinary Master’s Insert

Short description of case study

Further Reading and References

Document by Dewey:

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan Company.