Home / Course Design / Learning Objectives

Step 1: Define Learning Objectives

Did you know that writing specific and measurable learning objectives is more challenging than expected?

Common mistakes include the selection of inappropriate learning levels (active learning verbs), misalignment between what is stated (intended) and what is actually facilitated in the course or vague descriptions that ensure transparent assessment is near impossible. Carefully work through this page to ensure you make a good start!

Getting Started - selecting appropriate active learning verbs

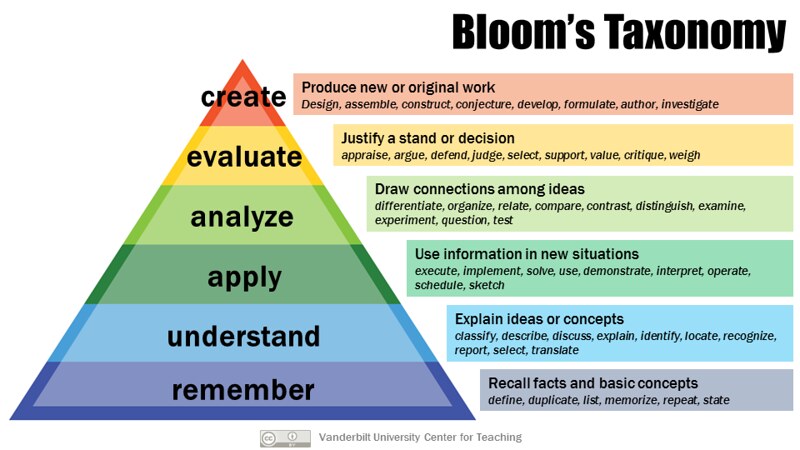

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a starting point, we recommend that you decide at which level (remember, understand, apply, analyse, evaluate, create) you wish your students to practise and demonstrate their learning. Bloom’s Taxonomy can help you to formulate your learning objectives; it can help you choose the right level and the right learning activities for your students. How? By following these steps:

- Determine the level of your students with help from the taxonomy. You can start from anywhere on the pyramid, however it depends on the prior knowledge of the students. Are they novices, i.e. on more of a remember/understand level, or do they already posses foundational knowledge and on an analyze/evaluate level?

- Determine what your students should be able to do after your course. For example, you want them to be able to apply and analyze. You can then use one of the active learning verbs that are mentioned at that specific level

Let’s look at an example:

- You conclude that your master students already remember and understand the basics. So you can skip the first two levels of Bloom. You want your students to be able to apply, analyze and evaluate.

- You can use the active learning verbs that are mentioned at these levels to formulate your learning objectives, for example: The student is able to contrast … within the context of …

Within an interdisciplinary course, if your students have less epistemic stability, they might be better suited to the lower Bloom’s levels. However, each context is different and especially within an interdisciplinary setting, students are challenged to take perspectives, incorporate different approaches and think critically, so higher Bloom’s levels can be considered here. For further reading on Bloom’s taxonomy and general information on learning objectives, see the sites below:

- Vanderbilt University provides a detailed explanation of Bloom’s Taxonomy – an essential element when composing learning objectives.

- DePaul University‘s site provides a comprehensive guide on learning objectives and outcomes.

Additional Theory - Constructive Alignment

Constructive alignment is a fundamental approach and a key theory in educational design. As with the first three steps of backward design, constructive alignment starts with articulating the appropriate learning objectives, deciding upon the assessment, then planning the learning activities. Making explicit at which level (active learning verbs) and focusing your planning on what and how students will learn, is essential. The learning activity is chosen carefully to ensure is it conducive to reaching the intended outcomes and is assessed in a valid manner, in line with the activity. Examples below, demonstrate the concept.

Biggs (1996), recommends 4 steps for designing of teaching, in order to enhance alignment:

- Define the learning objective on what students can do and know and to what standard.

- Ensure the learning environment is conducive to engaging the students in learning activities that will bring about the intended outcomes.

- Select assessments that match the intended outcomes, and that allow for judgement on variations in students’ performances in meeting the criteria.

- Translate these judgments into summative grades and/or feedback.

1. ILO: By the end of this (study unit) students are able to… Describe the multiple disciplinary perspectives applicable within the group challenge, through X (for example: role play or facilitated discussion). (The action verb ‘describe’ is on the lower level of Blooms’ Taxonomy level and is appropriate for this novice level; being introduced to the various disciplinary approaches in the team.)

2. Learning activity: here, the learning activity of a ‘facilitated or scaffolded discussion’ or ‘role play’ is a suitable activity to reach the ‘describe’ level ILO; students are prompted to ask critical questions, formulate appropriate responses, etc.

3. Assessment: in order to assess the student’s ability to describe the multiple disciplinary perspectives within the group, a presentation could be required to accompany the project product. Criteria can be graded according to a descriptive rubric that delineates the various levels of achievement.

4. Translate: Formative feedback can be given during the learning activity by educators and peers, and summative feedback can be in the form of a grade via the rubric, or simply the feedback descriptor from the rubric.

1. ILO: By the end of this (study unit) students are able to… explain another approach to a given problem. (Learning activity is not indicated, action verb ‘explain’ does not indicate in which form. ILO is not specific enough nor measurable.)

2. Learning activity: No specific facilitation – Students are put into groups and teachers assume students will incidentally attain this ILO.

3. Assessment: Group project. (No specific assessment on development of interdisciplinary understanding; rather the project product is the focus, not the process.)

4. Translate: Summative grades for the product only; there is no measurement or assessment of the student’s ability to explain another disciplinary approach, or gauge advancement in interdisciplinary understanding.

Interdisciplinary Specific Learning Objectives

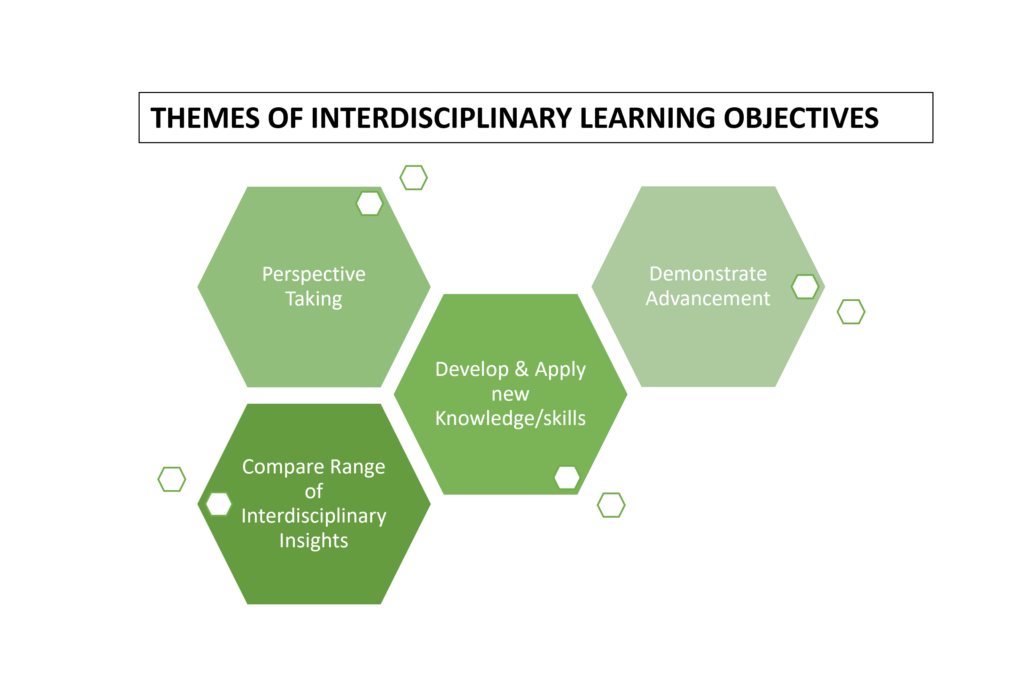

Interdisciplinary learning objectives also need to be composed of appropriate active learning verbs that are conducive to reaching the desired levels of cognitive advancement for our students. In order to select these appropriate active learning verbs, characteristics of interdisciplinarity characteristics need to be defined. A list of ideal interdisciplinary characteristics have been collated by Repko (2008), they are as follows:

- Ethical sensitivity, enhanced perspectives, creative and unconventional thinking, humility, listening skills & sensitivity to bias (Newell, 1990).

- Tolerance of ambiguity, critical thinking, ability to demythologise experts, enhanced empowerment. (Field, Lee & Field, 1994).

- Ability to synthesise/ integrate (Rhoten et al., 2006).

Based on these and for our purposes, we created a more focused and measurable characteristics or themes of interdisciplinary learning objectives. As you will see, the focus is primarily on the interdisciplinary process of learning. Team skills such as communication and collaboration have not been included here as they can also be generic and sourced elsewhere.

- Describe the multiple disciplinary perspectives applicable within the group challenge, through X (for example: role play or facilitated discussion).

- Reflect upon advancement in perspective taking abilities through the composition of X (for example: self-composed concept maps, personal logs ) near the beginning and again at the end of the course.

- Actively interrogate teammates or other sources (for example: formally through checklists, verbally) on their disciplinary approaches that are foreign/ new to them.

- Deconstruct the (project) challenge according to the disciplines within the team, (for example in a report, presentation) then co-construct feasible (checked through rubrics) propositions for the solution (for example: prototype with accompanying Gantt chart, or live demonstration of prototype justifying integrated aspects.)

- Critically analyse, via X (for example: a SWOT analysis, reflection activity) their own discipline’s approach (knowledge and processes) to the (project) challenge or case study.

- Compare and merge best practices from teammates’ analyses using X (comparison framework, debate script).

- Accurately recall key knowledge and processes of other disciplines within the team via X (discussion, role play) within a real or fictional scenario.

- Demonstrate epistemic stability in an adaptable manner through X (for example: arguments for their disciplinary contributions as well as acknowledging the benefits of others’ disciplinary approaches in report, presentation).

- Plan various alternative configurations and uses of disciplinary strengths from within the team, by X (for example: brainstorming, case study analysis) to propose possible causes/solutions of a (project) challenge.

- Evaluate and reverse engineer a product or perform analysis of policy (for example: using a framework, guiding questions prompts) related to team (project) challenge.

- Explain via X (for example: reflection report, reflective sound bite) how disciplinary expertise is combined in the solution to the case study/ (project) challenge.

- Reflect upon personal development of knowledge/perspectives over the (project) challenge process, by keeping a

progress diary/ log. - Record additional approaches learnt via pre and post self-analysis, comparison reports.

- Exemplify changes/enhancement of knowledge and skills through for example a reflective visual album.

- Identify starting weaknesses/ gaps in knowledge and skills, set SMART goals to address these gaps and actively develop these through peer learning, self-learning and demonstration (for example: evidence gathered in form of a learning portfolio.)

- Clearly articulate our interdisciplinary learning objectives;

- Check whether how we wish to assess them is valid and aligns with the level of the learning activity;

- Ensure planned learning activity is conducive to reaching the ILOs.

Further Reading

Book by Biggs & Tang:

Biggs, J and Tang, C. (2011): Teaching for Quality Learning at University. McGraw-Hill and Open University Press, Maidenhead.

Book by Frodeman:

Frodeman R. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity. Oxford University Press (Chapter 19).

Site – page by Armstrong:

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.